Nevoeiro

by Catarina de Oliveira Simão

by Catarina de Oliveira Simão

“In Portugal, a living riddle predicts the return of a long-lost king, gone missing after being injured in a battle. It is said that, on nebulous days, you can almost see him through the thick air, adrift in the fog of a forgetful country. This piece is about the battles of ordinary people.

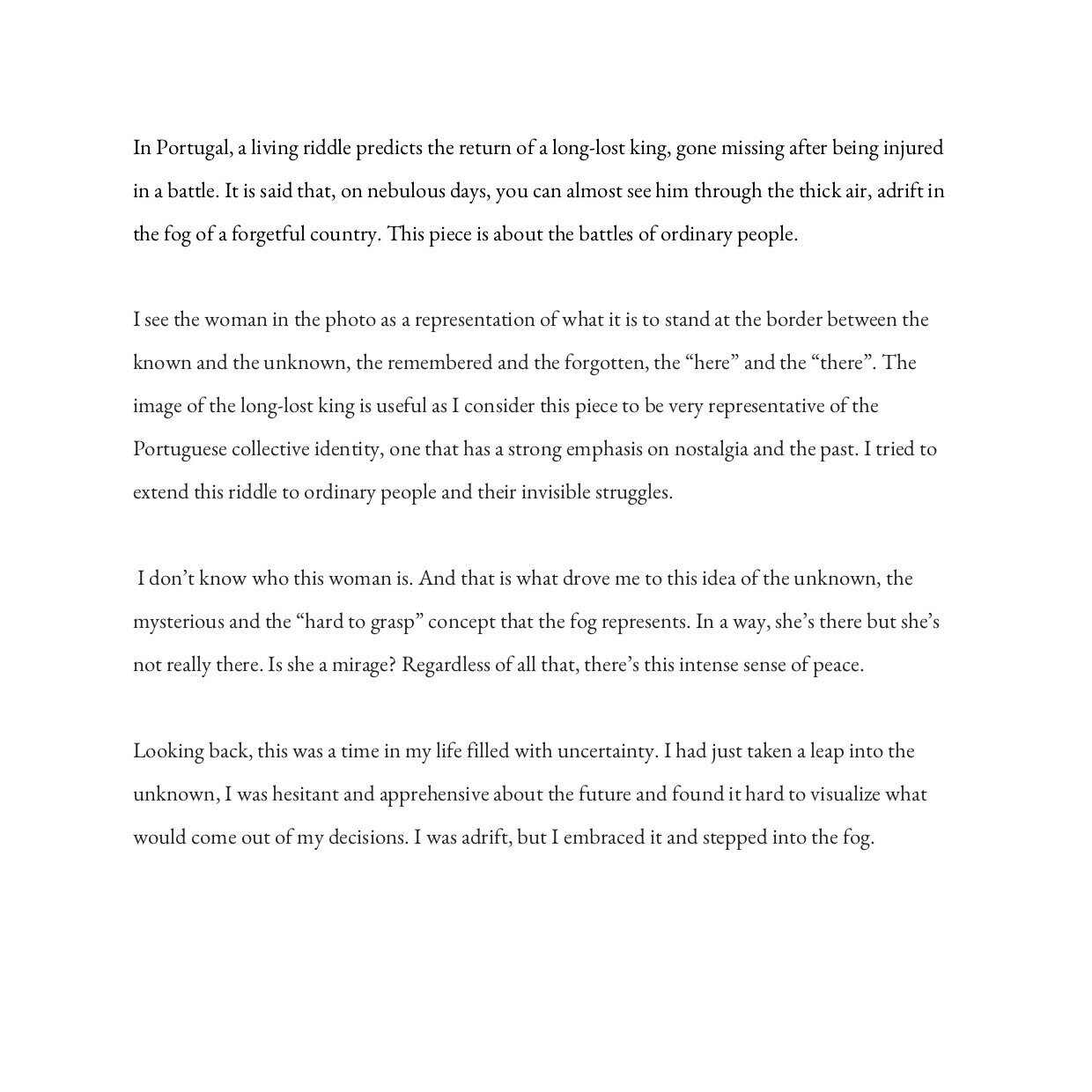

I see the woman in the photo as a representation of what it is to stand at the border between the known and the unknown, the remembered and the forgotten, the “here” and the “there”. The image of the long-lost king is useful as I consider this piece to be very representative of the Portuguese collective identity, one that has a strong emphasis on nostalgia and the past. I tried to extend this riddle to ordinary people and their invisible struggles.

I don’t know who this woman is. And that is what drove me to this idea of the unknown, the mysterious and the “hard to grasp” concept that the fog represents. In a way, she’s there but she’s not really there. Is she a mirage? Regardless of all that, there’s this intense sense of peace.

Looking back, this was a time in my life filled with uncertainty. I had just taken a leap into the unknown, I was hesitant and apprehensive about the future and found it hard to visualize what would come out of my decisions. I was adrift, but I embraced it and stepped into the fog.”

Catarina has loved photography since she can remember and could be frequently caught stealing her mom’s camera as a kid and use it to capture everyday snippets of their country-side life. More recently, she has started exploring film photography and has fallen in love with the grains and the textures it produces. She is undoubtedly an amateur but one with a wandering eye.

Testament and Q&A

by Kateryna Pavlyuk

by Kateryna Pavlyuk

“This photo series documents a surreal summer in Ukraine, in a year when Christenings were conducted in masks and affection was necessarily expressed through distance, rather than proximity. Although unpopulated, these photos carry the imprint of people on the homes they are confined to and testify to the solace that religion offers to many in dark times.”

A self-taught photographer and Goldsmiths-taught filmmaker, Kateryna’s work focus on reframing the quotidian and is underpinned by a fascination with composition and how the camera lens can see in ways our eyes cannot. Kateryna’s photography has previously featured in various student magazines, journals, and exhibitions, and has been shortlisted in London Photo Festival competitions.

Q&A with contributor by Dimitar Dimitrov

From my understanding, you're from Ukraine. Did you grow up there, and if yes, can you describe your experience and your religious background?

I was born in Ukraine but was actually raised in the UK. We moved when I was three and I wish I could say I remember my early years in Ukraine, but I’d be lying. My ‘memory’ of my first years in Ukraine is informed pretty much entirely by a single cassette of film, and even then it only fills in one day; my parents borrowed a camcorder from a relative for a single day and filmed me voraciously for 24 hours. I think my mum wanted to showcase my entire wardrobe in this single day, so the film features an absurd number of outfit changes. Even though I do very little, it means a lot to have these select, grainy snippets to fill the gaps in my early memory.

Although I grew up in the UK, in South London specifically, I was raised in a deeply Ukrainian home, so even on the opposite end of Europe, I was still surrounded by the language, food and culture of Ukraine. With regards to religion, I’m not religious myself. I was raised Catholic but disconnected with religion in my teens. That said, my parents remain religious and I’m deeply appreciative of and fascinated by faith.

What was your inspiration behind this photo series?

Every summer I visit my extended family in Ukraine and I always document these summers, through film and photography. It goes without saying that this summer was different. We didn’t think we would make the trip this year, but a number of important family events were planned – weddings, christenings – that we didn’t want to miss. These summer reunions are always saturated with affection, almost as if to make up for the entire year we’re all apart. This summer – just like everyone the world over – we had to try and express this affection over two metre distances and in masks. This series tries to capture that experience without actually photographing any masks, distanced crowds or, indeed, any people at all.

How has growing up in your environment affected your photographic vision and perhaps this series in particular?

I think the very fact that I haven’t grown up in Ukraine is a huge part of why I have this urge to document everything when I’m there. Relatives always raise eyebrows or laugh at me for photographing something deeply mundane in their eyes, but for me everything takes on an uncanny quality, of being familiar but not quite native. In this series especially, I wanted to preserve the additionally surreal quality that every room, event and interaction took on this summer. The hope is that next summer, I won’t be able to recreate any of these photos of unnerving, empty spaces, because every corner of every house will be filled with people and life.

In your submission you explain that 'Christenings were conducted in masks and affection was necessarily expressed through distance, rather than proximity' and that distance and isolation is indeed visible in your photographs. How did COVID affect your photography approach and your perspective when creating this series?

My photos from Ukraine are usually densely and intimately peopled – full of portraits and gatherings. This year I had to take a step back from everyone and so I turned my lens to lived and local spaces instead, which have become the parameters of people’s worlds. It was initially difficult to produce photos which were anything other than run-of-the-mill cityscape shots and flat images of a flat’s interiors, but I then noticed a recurring, albeit unplanned, motif in all my photos: religion. Despite the huge public health risk, many religious services continued and people were spilling out onto the streets outside churches on Sunday mornings. It’s easy to condemn this as reckless behaviour – and I’m certainly no advocate – but this speaks volumes about quite how important religion is to people, and I wanted the series to capture the significant role religion plays there, even and perhaps especially now.

Can you also expand a bit further on the role religion plays in your country and why it appears to be a motif in this series?

Ukraine is a deeply Christian country, and although that might be shifting now with younger generations, faith remains central to so many people’s lives and ways of living. I’m often frustrated by the hypocrisies this sometimes gives rise to, but I know and understand that, for so many, the church offers so much – be that community or hope. As I mentioned above, I didn’t necessarily set out to have religion as one of my motifs, but I soon found I could rarely take a photo in which this theme didn’t feature. Once I then began seeking out these religious elements myself, the series came together pretty organically.

Apocalypse

by Clotilde Nogues

by Clotilde Nogues

“By looking back at those pictures, it kind of jumped out at me. What if this was ‘The World Afterwards’, the one we’ve been imagining, fantasizing, and overthinking about during lockdown. What if we were left to ourselves after all this, not being able to live civilized as we used to, packed in cities. Would it look like that?

Devoid of human contact and sociability, we could let go little by little. Struggling from this new life, discovering new environments, and finally, rest. Return to our wilderness.”

Clotilde is a 23 year-old French girl who likes to captivate the human in his moments of freedom : (half) naked in nature. Some might struggle while others might enjoy it or just be curious about how it feels. Let’s discover it together.

Q&A WITH CONTRIBUTOR BY DIMITAR DIMITROV

Why do you like to capture the human form in a stripped and bare way?

To my opinion and beliefs, nudity is a representation of freedom. It shows the man in its purest authenticity, released from artifacts and associations. I think nudity shows a certain lightness and strength at the same time. Lightness for its natural and simple side, strength for its raw and audacious side to show what is. With this said, I capture the human in a stripped and bare way because that’s where I get inspiration.

There's a rawness and a graciousness in the photos with female subjects. How do you think your work illustrates the female experience in our world? What do your photographs say about being a woman perhaps?

I actually didn’t think about the female experience while taking the picture. I did think about it when thinking about publishing it. The person in the picture actually doesn't like one of them because she’d like her body to be different, to be more « perfect ». I think those imperfections are what makes it raw and true. The pictures don't lie and that’s what I like. It shows authentic woman bodies, assumed.

Are you afraid that the female subjects in your photos could be objectified or sexualised by a certain audience? Or are you perhaps conveying a non-erotic experience of the freedom of a human being in their pure form?

I am not afraid the female subject could be objectified or sexualized. Being afraid of that would be a step backwards I think. I can’t stop anybody from doing it though, but being free of showing the woman's body could also help people to think about it in another way maybe. The more we hide our bodies the more it gets eroticized or fantasized. So to show it is also a way to normalize it.

Is this how you envision the world after the pandemic is over?

I have many visions of the world after the pandemic is over. This one is one yes. It could be. « Nature regains its rights » and the human, devoid of his urban dweller attributes, rediscovers what it is to live connected with his environment.

Would you say your photographs reflect on a personal desire for escapism and discovery? How drawn are you to nature and the wilderness and how do your photographs potentially reflect that?

Yes totally. My photographs reflect this desire for escapism, wilderness, discovery... I think the moments in my life I felt the most happier and fulfilled were the ones where I was close to nature, free from work and city life. That's also the moment I like to shoot the most, where I am the most inspired. In those environments, I feel letting go from all thoughts and I have then a virgin ground to experiment.

Wells Blog

Duis mollis, est non commodo luctus, nisi erat porttitor ligula, eget lacinia odio sem nec elit. Maecenas faucibus mollis interdum. Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue.